THE LINCOLN HIGHWAY

recommended reading from Cybil at Goodreads

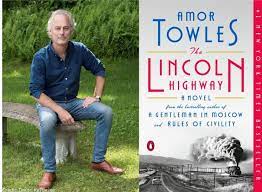

THE LINCOLN HIGHWAY by Amor Towles

and Norman Warwick can see why

When author Amor Towles published his second novel, A Gentleman in Moscow, in 2016, everything changed.

Towles’ first novel, Rules of Civility, was well-received and successful enough that it allowed Towles to retire from his career in finance and write full-time. But Gentleman basically went supernova, selling 1.5 million copies in hardback and earning rave reviews across the board.

It was a pleasant turn of events, to be sure, but it has also set up great expectations for Towles’ new book, The Lincoln Highway, which hits shelves this month. We’re happy to report that those great expectations have been entirely fulfilled.

The Lincoln Highway is, at once, a lovely set of character studies, a classic road trip odyssey, and a meditation on a very specific time in the American experiment. In June 1954, in nowhere-at-all Nebraska, we meet brothers Emmett and Billy, teenage fugitives Duchess and Woolly, professional hobo Ulysses, stalwart friend Sally, and the mysterious Professor Abernathy. Between Nebraska and New York City, we’re treated to some harrowing boxcar adventures, a remarkably compelling circus performance, and the curious tale of the world’s slipperiest 1948 Studebaker Land Cruiser. Oh, and the tornado story.

In fact, The Lincoln Highway is packed with stories—tales nested within yarns packed with legends. Central to the entire endeavor is a fictional tome you’ll want to read yourself: Professor Abernathy’s Compendium of Heroes, Adventurers, and Other Intrepid Travelers.

Speaking via Zoom from his home in Manhattan, Towles spoke with Goodreads contributor Glenn McDonald about his writing process, America in the 1950s, and the enduring majesty of the teenage spirit.

Goodreads: Your previous book, A Gentleman in Moscow, was a huge critical and commercial success. You’ve said that the idea for that book boiled down to one simple sentence. Was there a similar process with The Lincoln Highway?

Amor Towles: Yes, that’s been true for all my books—an idea or a sentence that I dwell on for a long period of time. In this case, I had this image of a kid coming home from a juvenile work camp, being driven by the warden to the family farm—but with two other kids from the farm hidden in the trunk of the car.

I don’t know where that one came from, actually. Usually, I kind of know the thing that triggered it. With A Gentleman in Moscow, it was walking into a hotel and having the thought about living permanently in a hotel. Sometimes these little sentences present themselves, and occasionally one or two will just capture my imagination enough that I start to think it through in greater detail. Who are these people? Where are they? When is this?

I knew a lot about this book in the first 72 hours. I knew that it was set in the Midwest and in the 1950s. The mother is gone, there’s a younger brother—it all starts to fall into place. Within the first couple of days, I knew Duchess, I knew Emmett, I knew Billy. I knew the Abernathy book and the train ride and the circus. Then I take that scaffolding, and I really start to think about it, over a period of years.

GR: Isn’t that fascinating? All of this is coming down from some pre-rational place, even the 1950s setting. The time frame was part of the package from moment one?

AT: Pretty much. You know, having since spent a lot of time writing the book—outlining it, drafting it, editing it—it’s only now that I have some clarity for myself about why I chose the 1950s. When I started, it was instinctive—as you say, a kind of pre-conscious decision.

But in retrospect, it occurred to me that this period was a moment of quietude for America. The Korean War is just ending, World War II is over. The turmoil of the ’30s is the Depression, the turmoil of the early ’40s is the Second World War. Suddenly you have this moment in America where it’s quiet, everything’s going well.

But at the same time, all this other stuff is about to come blasting in. The modern wave of civil rights activity is about to begin. Rock ’n’ roll is invented in 1954, which is really the first youth movement in the history of the world. There had never before been a massive expression of collective teenage opinion and sentiment until rock ’n’ roll in the United States. The American highway system was launched around ’54 or ’55, and the sexual revolution is about to happen, which will totally change sexual behaviour in America. It all subconsciously generates the sense of anticipation, that this giant wave is about to crash.

So there’s a simplicity to that moment of time in America. Setting the story in the 1950s let me avoid the stuff that would be overwhelming. It allowed the book to really be about the characters. It’s like the way that a Chekhovian play is set in the countryside. Chekhov knew what Moscow life was like, he knew what St. Petersburg life was like. With The Cherry Orchard, part of the reason he’s there in the country is because it pushes all that back. It allows him to focus on the interactions between the individuals—their personalities, their dreams, their personal history.

GR: Well, the characters are extremely lovable. I found that I became really emotionally attached to young Billy. Can you talk a little bit about Billy and Emmett, and that central relationship between the brothers?

AT: Right from the beginning, I had this notion that Emmett would be this kind of honorable, practical, Midwestern farm type. A little square, maybe. And I knew that he was going to have a little brother to take care of. Pretty quickly, I began to imagine Billy, and to hear him, and to think of the two of them together.

In modern parlance, we would probably say that Billy is on the [autism] spectrum. The great thing about the spectrum as a concept, of course, is that it represents an enormous array of behavioral and emotional attributes. And an individual can be anywhere on this broad spectrum. In the case of Billy, he’s very literal, and when things get intense, he withdraws. He’s a little OCD, maybe.

You know, it’s funny, so much of the writing process is the discovery of the humanity within your characters. You hope you’re going to get it right, but you don’t always. The discovery can often be triggered by something weird. In this case, the key was how Billy took off his backpack. I deliberately describe it in this very detailed way—taking it off and pulling out the strap and taking something out. Then putting it back and restrapping and putting it on his back. This is Billy’s way

GR: I remember talking to author Tana French a couple years back, and she said something that was really eye-opening. She said that when she writes from the point of view of a particular character, it impacts everything else about the story, even down to the descriptions of what might be in a particular room. She said she gets “behind the eyes” of her character to the point that she is only noticing what the character would notice. I just wondered if that sounded familiar to you?

AT: Oh, absolutely. The four or five central characters in this book, walking into a room, they would all see very different things. The first thing they look at would be different, the conclusions that they draw about that thing would be very different, and what it triggers in their own thoughts. That’s actually how you hope to bring that character to life for the readers. They can hear the different psychology, the different set of emotions, the different ambitions of that person through the way that they’re talking about something very simple.

GR: Each of the chapters in The Lincoln Highway is told from a different character’s point of view. Duchess’ chapters are written in first person, and I think maybe Sally’s, too. Why was it easier, in the case of those two characters, to switch to the first person?

AT: When I first outlined the book, each chapter was to be either Emmett or Duchess, and it would go back and forth. But after I got well into writing the book, other characters wanted to be telling their own thing—like Ulysses and Pastor John. And once that Pandora’s box was opened, then everybody wanted to be heard. It was like, now I have permission to go back and let Sally have her say and let Woolly have his say.

With Duchess, he’s very much a personality-driven voice, and you kind of need first person, because he’s also unreliable. He’s tricky and he’s charming. You want to hear what he’s been through in his own voice. So that seemed very natural. With Sally, I just had to trust my instincts. She had to be first person because that’s how I heard her in my own head.

GR: It seems that idea of “story” is important in this book. Each of the characters ends up telling other stories within their chapters, and you have this book of mythological stories driving the action. The effect is this cascade of stories nested within stories. Was that intentional?

AT: Well, again, this is a retrospective, but I think one of the reasons that stories are important in the book is that these characters are all around 18 years old. Emmett is 18, Duchess is 18, Sally’s maybe 19, Willie is 20 but claims to be 18. They’re all in that zone where, as young adults, we are beginning to fashion our own ethos. As a kid, you’re kind of given an ethos by your parents, by your community, by the school, or by the church. But around age 18, you take what you’ve been given and you start to make decisions about what is actually going to be your own lasting effort

And stories are an important source for all this. Whether they’re from the Bible or mythology, or the novels that we’ve read or stories that have been handed down through the family. These are among the ways in which we craft what our ethos is going to be. And these characters—they’re all changing each other’s stories in real time.

GR: Were you into stories and reading as a little kid?

AT: So, I became interested in reading and writing at the same time. In first grade, that’s when I decided I would like to write poetry or fiction or whatever. But I guess I was maybe nine or ten when books really started to consume a lot of my time. I think my dad gave me the first book of the Hardy Boys. I read it and I was like—oh, this is awesome. Then on the back of the book, there was this whole list of other books! And they were even numbered.

I remember my dad saying, Well, when you finish this one, if you want to read the next one, I’ll get it for you. So, we go back, and I read the next one the next day—and the next day and the next day. I think that’s when I realized this was a passion. I was no longer interested in going and doing what the family was doing. I wanted to sit and finish the book.of keeping an orderly

GR: How about in your teenage years, do you recall any particular books or authors that really hooked you then?

AT: Which year? Because 13 and 18 are very different times.

GR: Let’s go with 18, since we were just talking about that.

AT: Well, the beginning of age 18 to the end of age 19, that two-year period, was the first time I read Thoreau. That had a huge influence on me. It was the first time I read Dostoevsky, or any of the Russians, and those had a big influence on me. On the Road by Jack Kerouac, I guess, was around that time. I think I read One Hundred Years of Solitude right around then. All of those books continue to influence me. Not so much On the Road, ironically, considering what we’re talking about.

But those early books all continue to have an influence on me, both as a writer and a reader, but also just as a person, too. That was a very active, very rich time in that sense.

GR: Is there anything in particular you’d like to say to readers who might want to pick up The Lincoln Highway?

AT: Hmm, well, there is one thing with this book. I like to write different kinds of books, you know. And with this one, at some point I realized—and I said this to my publishers—this book is going to be a little darker, a little more challenging. This may find a smaller sliver of my reading audience. This book comes from a different place than, say, A Gentleman in Moscow. And I really do appreciate when my readers understand that, when they give my book enough time to let it do its own thing, to let the characters earn their keep. That’s a real gift to me.

Oh, also, as an aside—and I think the Goodreads community will enjoy this—there is a meaningful overlap between Rules of Civility and The Lincoln Highway. You don’t have to read one to enjoy the other, but if you’ve read Rules, you might spot some familiar elements. Fans may enjoy seeing how these threads from 1938—which is when Rules takes place—resurface in the mid-1950s in a very different context.universe.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!