JIMMY BUFFETT TAKES THE LAST BOAT HOME

Geoffrey Himes pays wonderful tribute as

JIMMY BUFFETT TAKES THE LAST BOAT HOME

and Norman Warwick learns more

It took me a while. The first tracks I ever heard by Jimmy Buffet was Pencil Thin Moustache, that somehow irritated me in the same way as Gallo Del Cielo by Tom Russell also drove me to distraction. I can´t be sure of the chronology of this, I never can be sure of chronology, but I think the first Buffett piece I fell in love with his version of his own He Went To Paris.

Rick Moore, writing in American Songwriter a few years ago also obviously admires the song, too. He wrote that ´Jimmy Buffett is probably best known to the general public for the hit “Margaritaville” and its namesake restaurants, and for a sense of humor and irony exhibited in songs like “Cheeseburger In Paradise” and “Why Don’t We Get Drunk (And Screw)” (which has had the words “and screw” dropped from the title by a lot of online retailers and websites). But what often escapes the notice of so many is that this guy really is an accomplished, and often very serious, songwriter with hundreds of original titles to his credit. His songwriting gift showed up early in pieces like the much-lauded 1973 story song “He Went To Paris.”

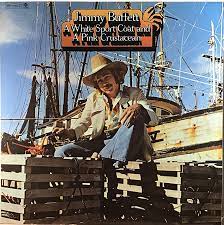

From his album A White Sport Coat And A Pink Crustacean, Buffett wrote the third-person narrative “He Went To Paris” about a Spanish Civil War veteran and one-armed pianist he’d met named Eddie Balchowsky. Released as the album’s final single, it didn’t chart, but in recent years has become well known, especially since Bob Dylan named it as one of his favorites and Buffett began to perform it live. With an unusual construction, the song opens, and closes, with the lines, “He went to Paris/Looking for answers/To questions that bothered him so.” In between those lines are four long verses that chronicle a life of 86 years that saw war, music, tragedy and world travels, with the subject finally, gratefully and graciously, telling the singer, “Jimmy, some of it’s magic, some of it’s tragic/But I had a good life all of the way.”

Buffett himself explained the song’s origins on the buffettnews.com website. “The song was actually about a guy I met in Chicago and he was the clean-up guy at a club called the Quiet Knight [where several prominent singer/songwriter careers were launched]. He had one arm. And so he started telling me stories about his days fighting in the Spanish Civil War and when he got wounded he came back to Paris for his treatment. The song is more reflective of stories that this guy, Eddie (right). told me. All they did was accentuate the history in the books that I was familiar with from Hemingway and Fitzgerald. That song was written actually in Chicago of all places, and it was written based on the stories of Eddie. At that point I don’t believe I’d ever been to Paris. You put all that stuff together and mix it like a gumbo.”

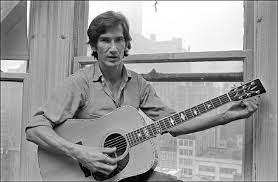

Not many writers can claim the honour of having the legendary Bob Dylan (left) as a fan. But in a 2011 interview with Bill Flanagan of the Huffington Post, when asked who some of his favourite songwriters were, Dylan said, “Buffett I guess. Lightfoot. Warren Zevon. Randy [Newman]. John Prine. Guy Clark. Those kinds of writers.” And when asked which Buffett songs he liked, Dylan replied, “’Death Of An Unpopular Poet.’ There’s another one called ‘He Went To Paris.’”

The original 1973 version of the song featured Buffett playing guitar along with another fine songwriter – from Chicago, oddly enough – the late Steve Goodman. The song was later covered by Waylon Jennings, and appears on several Buffett live and “best of” collections.

Another song I seem to remember falling in love with at about the same time is Chanson Pour Les Petit Enfants, that some people took as a Donovan ditzy, folksy, trippy song, a cousin Lucy in The Sky With Diamonds type images, but was in fact written for friends and their children.

Not everything Buffett wrote worked for me, and the parrot-head culture only sounded appealing on rainy Manchester days, but the best of, or my favourite, Buffetts are right up there at the top of all my playlists.

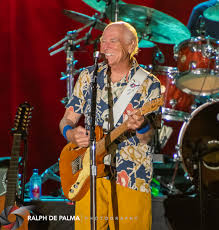

However, in his in-depth tribute to and assessment of the songwriter, Geoffrey Himes writing last week at Paste On Line, described Jimmy Buffett as the musician who built an empire out of the beach-bum lifestyle, died in hospice Friday at age 76 after a long battle with skin cancer. In many ways, his career paralleled that of the Grateful Dead (right). Each act personified a different brand of American hedonism: the Dead’s trucking and tripping in Northern California and Buffett’s sailing and drinking on the Gulf Coast.

“The culture along the Gulf Coast travels east-west,” Buffett told me in 1986. “You go 10 miles north and you’re in a different region. People who grow up along the coast like to eat, listen to music and have a good time. Most people live in a more complicated world, but when you get in a less complicated place, you find there’s only two things you really need: a good song and a good meal.”

Each act’s utopian fantasy inspired a fervent baby-boomer following; one group called themselves the Parrotheads, the other the Deadheads. One group wore a uniform of sunglasses and Hawaiian shirts, the other a uniform of ponytails and tie-dye shirts. Neither act had much luck on top-40 radio; they each had just one top-10 single: Buffett’s #8 “Margaritaville” in 1977 and the Dead’s #9 “Touch of Grey” in 1987. But both acts were powerhouses on the live-performance circuit, reliably selling out suburban sheds and basketball arenas.

Both acts were eventually scorned by later generations of hipsters and punks. Those critics identified some legitimate flaws, but they missed the undercurrent of tension in the best work of Buffett and the Dead. Beneath the visions of easy-going pleasure and transcendence was the worry that it was all precarious and could easily slip back into past problems or forward into future disappointments.

Even Buffett’s signature song “Margaritaville” reflected this dichotomy. The bouncy music and chuckling vocals celebrate the ability of that “frozen concoction” to cover up your problems, but those problems are all over the song: a bleeding foot from a pop top in the sand and romantic problems that are probably the singer’s fault.

This inner conflict is most obvious on “A Pirate Looks at Forty,” Buffett’s greatest song. Written for an older, marijuana-smuggling friend, the song has a wistful air, as if the young, seemingly carefree buccaneer inevitably becomes “an over-40 victim of fate … down to rock bottom again.”

Buffett was approaching 40 himself when Geoffrey Himes interviewed him in 1986.

“I never thought I’d make it this far,” he said, laughing. “But I’ve done more in 39 years than most people do in their whole life, so I’m looking forward to the second half.”

The second half proved very lucrative indeed. Between 1994 and 2006, he racked up six top-10 pop albums, including three Platinum and four Gold Records. He became the sixth writer to top both the fiction and non-fiction best-seller lists for The New York Times. His Margaritaville nightclubs opened in nine locations from Key West to Jamaica to New Orleans. But his best songwriting was behind him.

The rowdy party guy and the melancholy writer wrestled within Buffett from his adolescence on. He grew up in Mobile Alabama, where he was a former altar boy. While a senior in a Catholic high school there, he made his first trip to New Orleans.

“If you grew up in the Deep South,” he told me in 1986, “and you wanted to get into trouble, you headed for New Orleans. It was Sin City, and I knew where I wanted to go. I landed a summer job with a band and was living all those trashy novels. I love the romanticism of the French Quarter; I still have an apartment down there where I go when I need some quiet time to get my creative juices flowing.”

The city—as much a part of the Caribbean as of the Continental U.S.—fed the twin sides of the teenager’s dreams. On the one hand, it was a town where the partying went all night long—dancing, drinking and smoking till the crack of dawn. On the other hand, it was haunted by such wraiths as playwright Tennessee Williams (left) and novelist Walker Percy, who fed Buffett’s literary ambitions.

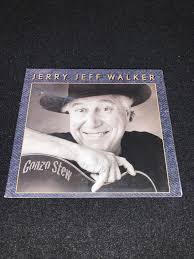

Along with friends such as Jerry Jeff Walker, Buffett wanted to be a country-folk singer in the Bob Dylan vein. Walker and Buffett even co-wrote a pretty good song together, “Railroad Lady,” but neither man was meant for understated, acoustic-guitar folk music.

“The folk music boom of the ’50s and ’60s barely touched New Orleans,” Chris Smither, the legendary songwriter for Bonnie Raitt, told me in 2014. “The Quorum Club on Esplanade had folk acts. I used to go down there to hang out. This guy Jerry Ferris played there, and I thought he was pretty good. Many years later I opened for him when he was calling himself Jerry Jeff Walker. But it was a fringe thing in New Orleans; it has always been a horn and keyboard town.”

Buffett was enamored of those funky horns and keys. “I was playing on Bourbon Street at the Bayou Room,” he told me in 1986, “and Art and Aaron Neville were down the street at the Ivanhoe. So we go back a long way. But once you get attached to the Neville Brothers music, you never let go of it.”

Buffett and Walker (left) were traveling together when a gig in Miami got cancelled. Walker suggested an impromptu trip to Key West, and Buffett fell in love with what he found. The little fishing village had both Ernest Hemingway’s house and bars where the talk and alcohol flowed all night. It was like New Orleans but with ready access to the ocean. He moved there and began writing songs about his newfound home.

After a small-label folk album that had sold only 324 copies at the time, Buffett signed with ABC-Dunhill Records. The first two Dunhill LPs were an uneasy mix of Key West and Nashville, but the third, 1974’s A1A, named after the highway that connected Miami to Key West, matched the words to the music perfectly and embodied Buffett’s evolving sun-and-fun ethos. It included the memorable tunes “A Pirate Looks at Forty” and “Trying to Reason with Hurricane Season.”

The breakthrough came two albums later on 1977’s Changes in Latitudes, Changes in Attitudes. “Margaritaville,” “Wonder Why We Ever Go Home” and the title track became anthems for the emerging Parrothead nation. The album reached #2 on the country charts and #12 on the pop charts.

After that, the live shows became more important than the records. And why not? They were reliably entertaining spectacles. Buffett was a fine tenor singer (much better than Jerry Garcia or Bob Weir) and his Coral Reefer Band was full of terrific musicians. One’s first encounter with the show was always the best, when the jokes, the vibe and the schtick were brand new. Subsequent concerts became somewhat predictable—in a way the Dead’s shows never did. The Dead might be underwhelming or transcendant, but you never knew what you were going to get.

As Buffett’s songwriting lost its inner drama, he became an underrated interpretive singer. Some of the best performances in his recorded catalogue are such covers as Jesse Winchester’s “Biloxi,” Steve Goodman’s “This Hotel Room,” Rodney Crowell’s “Stars on the Water,” Art Neville’s “Why You Wanna Hurt My Heart?” Ray Davies’ “Sunday Afternoon,” Bruce Cockburn’s “Pacing the Cage,” John Hiatt’s “Windows on the World,” Bill Withers’ “Playin’ the Loser Again,” Guy Clark’s “Boats To Build” and Mary Gauthier’s “Wheel Within the Wheel.”

Buffett also recorded two Grateful Dead compositions: “Uncle John’s Band” and “Scarlet Begonias.” The first tune is completely recast as a relaxed calypso tune, thanks to Robert Greenidge’s steel drums and Angel Quinones’ congas. The Dead’s lyricist Robert Hunter warned the listener that just “when life looks like Easy Street, there is danger at your door.” But don’t worry; Uncle John’s musicians are coming to take you from your troubles and bring you back home.

This kind of optimism in the face of crisis was right in Buffett’s wheelhouse and his sunny vocal eclipses Garcia’s and reminds us why he was so popular for so long. Forget about the long years of forgettable albums and soundalike tours, the franchised nightclubs and book deals. When Buffett could work his magic on a song like this, he deserved his place in the history of American music.

I have always wondered if Townes Van Zandt, in a good way, might be turning Heaven into a Hell of a place., and now I wonder whether Jimmy will buy some sea-front property there and throw barbies on Sundays.

cover

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The primary sources for this piece were written for the print and on line media by Rick Moore for American Songwriter and Geoffrey Himes for Paste On Line magazine. Authors and Titles have been attributed in our text wherever possible

Images employed have been taken from on line sites only where categorised as images free to use.

For a more comprehensive detail of our attribution policy see our for reference only post on 7th April 2023 entitled Aspirations And Attributions.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!