unknown OUTSIDE OF A SMALL CIRCLE OF FRIENDS

unknown

OUTSIDE OF A SMALL CIRCLE OF FRIENDS

says Norman Warwick

Philip David Ochs, (left) (/ˈoʊks/; December 19, 1940 – April 9, 1976) was an American songwriter and protest singer (or, as he preferred, a topical singer). Ochs was known for his sharp wit, sardonic humour, political activism, often alliterative lyrics, and distinctive voice. He wrote hundreds of songs in the 1960s and 1970s and released eight albums.

Ochs performed at many political events during the 1960s counterculture era, including anti-Vietnam War and civil rights rallies, student events, and organized labour events over the course of his career, in addition to many concert appearances at such venues as New York City’s Town Hall and Carnegie Hall. Politically, Ochs described himself as a “left social democrat” who became an “early revolutionary” after the protests at the 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago led to a police riot, which had a profound effect on his state of mind.

After years of prolific writing in the 1960s, Ochs’s mental stability declined in the 1970s. He eventually succumbed to a number of problems including bipolar disorder and alcoholism, and died by suicide in 1976.

Ochs’s influences included Woody Guthrie, Pete Seeger, Buddy Holly, Elvis Presley, Bob Gibson, Faron Young, and Merle Haggard. His best-known songs include “I Ain’t Marching Anymore“, “When I’m Gone”, “Changes”, “Crucifixion“, “Draft Dodger Rag“, “Love Me, I’m a Liberal“, “Outside of a Small Circle of Friends“, “Power and the Glory“, “There but for Fortune“, “The War Is Over“, and “No More Songs”.

Phil Ochs was born on December 19, 1940, in El Paso, Texas, to Jacob “Jack” Ochs, a physician who was born in New York on August 11, 1910, and Gertrude Phin Ochs, who was born on February 26, 1912, n Scotland.[6] His parents met and married in Edinburgh where Jack was attending medical school. After their marriage, they moved to the United States. Jack, drafted into the army, was sent overseas near the end of World War II, where he treated soldiers at the Battle of the Bulge. His war experiences affected his mental health and he received an honorable medical discharge in November 1945. Suffering from bipolar disorder and depression on his return home, Jack was unable to establish a successful medical practice and instead worked at a series of hospitals around the country. As a result, the Ochs family moved frequently: to Far Rockaway, New York, when Ochs was a teenager; then to Perrysburg in western New York, where he first studied music; and then to Columbus, Ohio. Ochs grew up with an older sister, Sonia (known as Sonny, born 1937), and a younger brother, Michael (born 1943). The Ochs family was middle class and Jewish, but not religious. His father was distant from his wife and children, and was hospitalized for depression; he died on April 30, 1963, from a cerebral hemorrhage. Phil´s mother died on March 9, 1994.

As a teenager, Ochs was recognized as a talented clarinet player; in an evaluation, one music instructor wrote: “You have exceptional musical feeling and the ability to transfer it on your instrument is abundant.” His musical skills allowed him to play clarinet with the orchestra at the Capital University Conservatory of Music in Ohio, where he rose to the status of principal soloist before he was 16. Although Ochs played classical music, he soon became interested in other sounds he heard on the radio, such as early rock icons Buddy Holly and Elvis Presley and country music artists including Faron Young, Ernest Tubb, Hank Williams Sr., and Johnny Cash. Ochs also spent a lot of time at the movies. He especially liked big screen heroes such as John Wayne and Audie Murphy. Later on, he developed an interest in movie rebels, including Marlon Brando and James Dean.

From 1956 to 1958, Ochs was a student at the Staunton Military Academy in rural Virginia, and when he graduated he returned to Columbus and enrolled in the Ohio State University. Unhappy after his first quarter, he took a leave of absence and went to Florida. While in Miami, the 18-year-old Ochs was jailed for two weeks for sleeping on a park bench, an incident he would later recall:

Somewhere during the course of those fifteen days I decided to become a writer. My primary thought was journalism … so in a flash, I decided—I’ll be a writer and a major in journalism.

Ochs returned to Ohio State to study journalism and developed an interest in politics, with a particular interest in the Cuban Revolution of 1959. At Ohio State, he met Jim Glover, a fellow student who was a devotee of folk music. Glover introduced Ochs to the music of Pete Seeger, Woody Guthrie, and The Weavers (right) . Glover taught Ochs how to play guitar, and they debated politics. Ochs began writing newspaper articles, often on radical themes. When the student paper refused to publish some of his more strident articles, he started his own underground newspaper called The Word. His two main interests, politics and music, soon merged, and Ochs began writing topical political songs. Ochs and Glover formed a duet called “The Singing Socialists”, later renamed “The Sundowners”, but the duo broke up before their first professional performance and Glover went to New York City to become a folksinger.

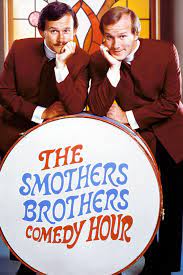

Ochs’s parents and brother had moved from Columbus to Cleveland, and Ochs started to spend more time there, performing professionally at a local folk club called Farragher’s Back Room. He was the opening act for a number of musicians in the summer of 1961, including The Smothers Brothers. Ochs met folksinger Bob Gibson that summer as well, and according to Dave Van Ronk, Gibson became “the seminal influence” on Ochs’s writing. Ochs continued at Ohio State into his senior year, but was bitterly disappointed at not being appointed editor-in-chief of the college newspaper, and dropped out in his last quarter without graduating. He left for New York, as Glover had, to become a folksinger.

photo 6 In the early 1960s, there was a folk music rebirth in the USA with the likes of Peter, Paul and Mary, Joan Baez, Pete Seeger and Bob Dylan. Although his fame was probably limited, Ochs became an integral part of that crowd. His songs “Draft Dodger Rag” and “I Ain’t Marching Anymore” became a rallying cry for the peace movement much the way that Dylan’s did.

Ochs arrived in New York City in 1962 and began performing in numerous small folk nightclubs, eventually becoming an integral part of the Greenwich Village folk music scene. He emerged as an unpolished but passionate vocalist who wrote pointed songs about current events: war, civil rights, labor struggles and other topics. While others described his music as “protest songs”, Ochs preferred the term “topical songs”.

Ochs described himself as a “singing journalist” saying he built his songs from stories he read in Newsweek. By the summer of 1963, he was sufficiently well known in folk circles to be invited to sing at the Newport Folk Festival, where he performed “Too Many Martyrs” (co-written with Bob Gibson), “Talking Birmingham Jam”, and “Power and the Glory“—his patriotic Guthrie-esque anthem that brought the audience to its feet. Other performers at the 1963 folk festival included Peter, Paul and Mary (right), Joan Baez, Bob Dylan, and Tom Paxton. Ochs’s return appearance at Newport in 1964, when he performed “Draft Dodger Rag” and other songs, was widely praised. However, he was not invited to appear in 1965, the festival when Dylan infamously performed “Maggie’s Farm” with an electric guitar. Although many in the folk world decried Dylan’s choice, Ochs was amused, and admired Dylan’s courage in defying the folk establishment.

In 1963, Ochs performed at New York’s Carnegie Hall and Town Hall in hootenannies. He made his first solo appearance at Carnegie Hall in 1966. Throughout his career, Ochs would perform at a wide range of venues, including civil rights rallies, anti-war demonstrations, and concert halls.[36]

Ochs contributed many songs and articles to the influential Broadside Magazine (left). He recorded his first three albums for Elektra Records: All the News That’s Fit to Sing (1964), I Ain’t Marching Anymore (1965), and Phil Ochs in Concert (1966). Critics wrote that each album was better than its predecessors, and fans seemed to agree; record sales increased with each new release.

On these records, Ochs was accompanied only by an acoustic guitar. The albums contain many of Ochs’s topical songs, such as “Too Many Martyrs”, “I Ain’t Marching Anymore“, and “Draft Dodger Rag”; and some musical reinterpretation of older poetry, such as “The Highwayman” (poem by Alfred Noyes) and “The Bells” (poem by Edgar Allan Poe). Phil Ochs in Concert includes some more introspective songs, such as “Changes” and “When I’m Gone”.During the early period of his career, Ochs and Bob Dylan had a friendly rivalry. Dylan said of Ochs, “I just can’t keep up with Phil. And he just keeps getting better and better and better”. On another occasion, when Ochs criticized either “One of Us Must Know (Sooner or Later)” or “Can You Please Crawl Out Your Window?” (sources differ), Dylan threw him out of his limousine, saying, “You’re not a folksinger. You’re a journalist.”

In 1962, Ochs married Alice Skinner, who was pregnant with their daughter Meegan, in a City Hall ceremony with Jim Glover as best man and Jean Ray as bridesmaid, and witnessed by Dylan’s sometime girlfriend, Suze Rotolo. Phil and Alice separated in 1965, but they never divorced.

Like many people of his generation, Ochs deeply admired President John F. Kennedy, even though he disagreed with the president on issues such as the Bay Of Pigs Invasion, the Cuban Missile Crisis, and the growing involvement of the United States in the Vietnamese civil war. When Kennedy was assassinated on November 22, 1963, Ochs wept. He told his wife that he thought he was going to die that night. It was the only time she ever saw Ochs cry.

Ochs’s managers during this part of his career were Albert Grossman (who also managed Dylan and Peter, Paul, and Mary) followed by Arthur Gorson, who had close ties with such groups as Americans For Democratic Action, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, and Students for a Democratic Society.

Ochs was writing songs at such a fast pace that some of the songs he wrote during this period were held back and recorded on his later albums.

In 1967, Ochs – now managed by his brother Michael—left Elektra Records for A&M Records and moved to Los Angeles, California. He recorded four studio albums for A&M: Pleasures of the Harbor (1967), Tape From California (1968), Rehearsals For Retirement (1969), and the ironically titled Greatest Hits (1970) (which actually consisted of all new material). For his A&M albums, Ochs moved away from simply produced solo acoustic guitar performances and experimented with ensemble and even orchestral instrumentation, “baroque-folk”, in the hopes of producing a pop-folk hybrid that would be a hit.

Critic Robert Christgau, writing in Esquire of Pleasures Of The Harbor in May 1968, did not consider this new direction a good turn. While describing Ochs as “unquestionably a nice guy”, he went on to say, “too bad his voice shows an effective range of about half an octave [and] his guitar playing would not suffer much if his right hand were webbed.” “Pleasures of the Harbor“, Christgau continued, “epitomizes the decadence that has infected pop since Sgt. Pepper. [The] gaudy musical settings … inspire nostalgia for the three-chord strum.” With an ironic sense of humor, Ochs included Christgau’s “webbed hand” comment in his 1968 songbook The War is Over on a page titled “The Critics Raved”, opposite a full-page picture of Ochs standing in a large metal garbage can.

Despite his sense of humour, Ochs was unhappy that his work was not receiving the critical acclaim and popular success he had hoped to achieve. Still, Ochs would joke on the back cover of Greatest Hits that there were 50 Phil Ochs fans (“50 fans can’t be wrong!”), a sarcastic reference to an Elvis Presley album that bragged of 50 million Elvis fans.

None of Ochs’s songs became hits, although “Outside of a Small Circle of Friends” received a good deal of airplay. It reached #119 on Billboard‘s national “Hot Prospect” listing before being pulled from some radio stations because of its lyrics, which sarcastically suggested that “smoking marijuana is more fun than drinking beer”. It was the closest Ochs ever came to the Top 40.

Joan Baez, however, did have a Top Ten hit in the U.K. in August 1965, reaching #8 with her cover of Ochs’s song “There but for Fortune”, (left) which was also nominated for a Grammy Award for “Best Folk Recording´ In the U.S. it peaked at #50 on the Billboard charts[]—a good showing, but not a hit.

Although he was trying new things musically, Ochs did not abandon his protest roots. He was profoundly concerned with the escalation of the Vietnam War, performing tirelessly at anti-war rallies across the country. In 1967 he organized two rallies to declare that “The War Is Over”—”Is everybody sick of this stinking war? In that case, friends, do what I and thousands of other Americans have done—declare the war over.”—one in Los Angeles in June, the other in New York in November. He continued to write and record anti-war songs, such as “The War Is Over” and “White Boots Marching in a Yellow Land”. Other topical songs of this period include “Outside of a Small Circle of Friends”, inspired by the murder of Kitty Genovese, who was stabbed to death outside of her New York City apartment building while dozens of her neighbors reportedly ignored her cries for help, and “William Butler Yeats Visits Lincoln Park and Escapes Unscathed”, about the despair he felt in the aftermath of the Chicago 1968 Democratic National Convention police riot.

Ochs was writing more personal songs as well, such as “Crucifixion”, in which he compared the deaths of Jesus Christ and assassinated President John F. Kennedy as part of a “cycle of sacrifice” in which people build up heroes and then celebrate their destruction; “Chords of Fame”, a warning against the dangers and corruption of fame; “Pleasures Of The Harbour”, a lyrical portrait of a lonely sailor seeking human connection far from home; and “Boy in Ohio”, a plaintive look back at Ochs’s childhood in Columbus.

A lifelong movie fan, Ochs worked the narratives of justice and rebellion that he had seen in films into his music, describing some of his songs as “cinematic”. He was disappointed and bitter when his one-time hero John Wayne embraced the Vietnam War with what Ochs saw as the blind patriotism of Wayne’s 1968 film, The Green Berets:

[H]ere we have John Wayne, who was a major artistic and psychological figure on the American scene, … who at one point used to make movies of soldiers who had a certain validity, … a certain sense of honor [about] what the soldier was doing. … Even if it was a cavalry movie doing a historically dishonorable thing to the Indians, even as there was a feeling of what it meant to be a man, what it meant to have some sense of duty. … Now today we have the same actor making his new war movie in a war so hopelessly corrupt that, without seeing the movie, I’m sure it is perfectly safe to say that it will be an almost technically-robot-view of soldiery, just by definition of how the whole country has deteriorated. And I think it would make a very interesting double feature to show a good old Wayne movie like, say, She Wore a Yellow Ribbon with The Green Berets. Because that would make a very striking comment on what has happened to America in general.

Ochs was involved in the creation of the Youth International Party, known as the Yippies, along with Jerry Rubin, Abbie Hoffman, Stew Albert, and Paul Krassner.[ At the same time, Ochs actively supported Eugene McCarthy‘s more mainstream bid for the 1968 Democratic nomination for President, a position at odds with the more radical Yippie point of view. Still, Ochs helped plan the Yippies’ “Festival of Life” which was to take place at the 1968 Democratic National Convention along with demonstrations by other anti-war groups including the National Mobilization Committee to End the War in Vietnam. Despite warnings that there might be trouble, Ochs went to Chicago both as a guest of the McCarthy campaign and to participate in the demonstrations. He performed in Lincoln Park, Grant Park, and at the Chicago Coliseum, witnessed the violence perpetrated by the Chicago police against the protesters, and was himself arrested at one point. Ochs also purchased the young boar who became known as the Yippie 1968 Presidential candidate “Pigasus the Immortal” from a farm in Illinois.[81][82]

At the trial of the Chicago Seven in December 1969, Ochs testified for the defense. His testimony included his recitation of the lyrics to his song “I Ain’t Marching Anymore”. On his way out of the courthouse, Ochs sang the song for the press corps; to Ochs’s amusement, his singing was broadcast that evening by Walter Cronkite on the CBS Evening News

After the riot in Chicago and the subsequent trial, Ochs changed direction again. The events of 1968 convinced him that the average American was not listening to topical songs or responding to Yippie tactics. Ochs thought that by playing the sort of music that had moved him as a teenager he could speak more directly to the American public.

Ochs turned to his musical roots in country music and early rock and roll.] He decided he needed to be “part Elvis Presley and part Che Guevara“, so he commissioned a gold lamé suit from Elvis Presley’s costumer Nudie Cohn. Ochs wore the gold suit on the cover of his 1970 album, Greatest Hits, which consisted of new songs largely in rock and country styles. Ochs went on tour wearing the gold suit, backed by a rock band, singing his own material along with medleys of songs by Buddy Holly, Elvis, and Merle Haggard. His fans did not know how to respond. This new Phil Ochs drew a hostile reaction from his audience. Ochs’s March 27, 1970, concerts at Carnegie Hall were the most successful, and by the end of that night’s second show, Ochs had won over many in the crowd. The show was recorded and released as Gunfight at Carnegie Hall.

During this period, Ochs was taking drugs to get through performances. He had been taking Valium for years to help control his nerves, and he was also drinking heavily. Pianist Lincoln Mayorga said of that period, “He was physically abusing himself very badly on that tour. He was drinking a lot of wine and taking uppers. The wine was pulling him one way and the uppers were pulling him another way, and he was kind of a mess. There were so many pharmaceuticals around – so many pills. I’d never seen anything like that.”[92] Ochs tried to cut back on the pills, but alcohol remained his drug of choice for the rest of his life.

Depressed by his lack of widespread appreciation and suffering from writer’s block, Ochs did not record any further albums. He slipped deeper into depression and alcoholism. His personal problems notwithstanding, Ochs performed at the inaugural benefit for Greenpeace on October 16, 1970, at the Pacific Coliseum in Vancouver, British Columbia. A recording of his performance, along with performances by Joni Mitchell and James Taylor, was released by Greenpeace in 2009.

In August 1971, Ochs went to Chile, where Salvador Allende, a Marxist, had been democratically elected in the 1970 election. There he met Chilean folksinger Víctor Jara, an Allende supporter, and the two became friends. In October, Ochs left Chile to visit Argentina. Later that month, after singing at a political rally in Uruguay, he and his American traveling companion David Ifshin were arrested and detained overnight. When the two returned to Argentina, they were arrested as they got off the airplane. After a brief stay in an Argentinian prison, Ochs and Ifshin were sent to Bolivia via a commercial airliner where authorities were to detain them. Ifshin had previously been warned by Argentinian leftist friends that when the authorities sent dissidents to Bolivia, they would disappear forever. When the airliner arrived in Bolivia, the American captain of the Braniff International Airways aircraft allowed Ochs and Ifshin to stay on the aircraft and barred Bolivian authorities from entering. The aircraft then flew to Peru where the two disembarked and they were not detained. Fearful that Peruvian authorities might arrest him, Ochs returned to the United States a few days later.

Ochs was having difficulties writing new songs during this period, but he had occasional breakthroughs. He updated his sarcastic song “Here’s to the State of Mississippi” as “Here’s to the State of Richard Nixon”, with cutting lines such as “the speeches of the Spiro are the ravings of a clown”, a reference to Nixon’s vitriolic vice president, Spiro Agnew—sung as “the speeches of the President are the ravings of a clown” after Agnew’s resignation.

Ochs was personally invited by John Lennon to sing at a large benefit at the University of Michigan in December 1971 on behalf of John Sinclair, an activist poet who had been arrested on minor drug charges and given a severe sentence. Ochs performed at the John Sinclair Freedom Rally along with Stevie Wonder, Allen Ginsberg, David Peel, Abbie Hoffman, and many others. The rally culminated with Lennon and Yoko Ono, who were making their first public performance in the United States since the breakup of The Beatles.

Although the 1968 election had left him deeply disillusioned, Ochs continued to work for the election campaigns of anti-war candidates, such as George McGovern‘s unsuccessful Presidential bid in 1972.

In 1972, Ochs was asked to write the theme song for the film Kansas City Bomber. The task proved difficult, as Ochs struggled to overcome his writer’s block. Although his song was not used in the soundtrack, it was released as a single.

Ochs decided to travel. In mid-1972, he went to Australia and New Zealand. He traveled to Africa in 1973, where he visited Ethiopia, Kenya, Tanzania, Malawi, and South Africa. One night, Ochs was attacked and strangled by robbers in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, which damaged his vocal cords, causing a loss of the top three notes in his vocal range. The attack also exacerbated by his growing mental problems, and he became increasingly paranoid. Ochs believed the attack may have been arranged by government agents—perhaps the CIA. Still, he continued his trip, even recording a single in Kenya, “Bwatue“.

On September 11, 1973, the Allende government of Chile was overthrown in a coup d’état. Allende committed suicide during the bombing of the presidential palace, and singer Victor Jara was rounded up with other professors and students, tortured and brutally killed.

When Ochs heard about the manner in which his friend Victor Jara (right) had been killed, he was outraged and decided to organize a benefit concert to bring to public attention the situation in Chile, and raise funds for the people of Chile. The concert, “An Evening with Salvador Allende”, was held on May 9, 1974, at New York City’s Felt Forum, included films of Allende; singers such as Pete Seeger, Arlo Guthrie, Dave Van Ronk, and Bob Dylan; and political activists such as former U.S. Attorney General Ramsey Clark. Dylan had agreed to perform at the last minute when he heard that the concert had sold so few tickets that it was in danger of being canceled. Once his participation was announced, the event quickly sold out.[108]

After the Chile benefit, Ochs and Dylan discussed the possibility of a joint concert tour, playing small nightclubs. Nothing came of the Dylan-Ochs plans, but the idea eventually evolved into Dylan’s Rolling Thunder Revue.

The Vietnam War ended on April 30, 1975. Ochs planned a final “War Is Over” rally, which was held in New York’s Central Park on May 11. More than 100,000 people came to hear Ochs, joined by Harry Belafonte, Odetta, Pete Seeger, Paul Simon and others. Ochs and Joan Baez sang a duet of “There but for Fortune” and he closed with his song “The War Is Over“—finally a true declaration that the war was over.

Ochs outside the offices of the National Student Association in Washington, D.C., in 1975

Ochs’s drinking became more and more of a problem, and his behaviour became increasingly erratic. He frightened his friends both with his drunken rants about the FBI and CIA and about his claiming to want to have Elvis’s manager Colonel Tom Parker or Kentucky Fried Chicken‘s Colonel Sanders manage his career.

In mid-1975, Ochs took on the identity of John Butler Train. He told people that Train had murdered Ochs and that he, John Butler Train, had replaced him. Ochs was convinced that someone was trying to kill him, so he carried a weapon at all times: a hammer, a knife, or a lead pipe.

His brother, Michael, attempted to have him committed to a psychiatric hospital. Friends pleaded with him to get help voluntarily. They feared for his safety because he was getting into fights with bar patrons. Unable to pay his rent, he began living on the streets.

After several months, the Train persona faded and Ochs returned, but his talk of suicide disturbed his friends and family. They hoped it was a passing phase, but Ochs was determined, One of his biographers explains Ochs’s motivation:

By Phil’s thinking, he had died a long time ago: he had died politically in Chicago in 1968 in the violence of the Democratic National Convention; he had died professionally in Africa a few years later when he had been strangled and felt that he could no longer sing; he had died spiritually when Chile had been overthrown and his friend Victor Jara had been brutally murdered; and, finally, he had died psychologically at the hands of John Train.

In January 1976, Ochs moved to Far Rockaway, New York, to live with his sister Sonny. He was lethargic; his only activities were watching television and playing cards with his nephews. Ochs saw a psychiatrist, who diagnosed his bipolar disorder. He was prescribed medication, and he told his sister he was taking it. On April 9, 1976, Ochs died by suicide by hanging himself in Sonny’s home.

Years after his death, it was revealed that the FBI had a file of nearly 500 pages on Ochs. Much of the information in those files relates to his association with counter-culture figures, protest organizers, musicians, and other people described by the FBI as “subversive”. The FBI was often sloppy in collecting information on Ochs: his name was frequently misspelled “Oakes” in their files, and they continued to consider him “potentially dangerous” after his death. Congresswoman Bella Abzug (Democrat from New York), an outspoken anti-war activist herself who had appeared at the 1975 “War is Over” rally, entered this statement into the Congressional Record on April 29, 1976:

Mr. Speaker, a few weeks ago, a young folksinger whose music personified the protest mood of the 1960s took his own life. Phil Ochs – whose original compositions were compelling moral statements against the war in Southeast Asia – apparently felt that he had run out of words.

While his tragic action was undoubtedly motivated by terrible personal despair, his death is a political as well as an artistic tragedy. I believe it is indicative of the despair many of the activists of the 1960s are experiencing as they perceive a government that continues the distortion of national priorities that is exemplified in the military budget we have before us.

Phil Ochs’s poetic pronouncements were part of a larger effort to galvanize his generation into taking action to prevent war, racism, and poverty. He left us a legacy of important songs that continue to be relevant in 1976—even though “the war is over”.

Just one year ago – during this week of the anniversary of the end of the Vietnam War — Phil recruited entertainers to appear at the “War Is Over” celebration in Central Park, at which I spoke.

It seems particularly appropriate that this week we should commemorate the contributions of this extraordinary young man.

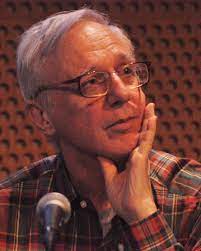

Robert Christgau, (left) who had been so critical of Pleasures Of The Harbour and Ochs’s guitar skills eight years earlier, wrote warmly of Ochs in his obituary in The Village Voice. “I came around to liking Phil Ochs’s music, guitar included,” Christgau wrote. “My affection [for Ochs] no doubt prejudiced me, so it is worth [noting] that many observers who care more for folk music than I do remember both his compositions and his vibrato tenor as close to the peak of the genre.”

I could have written this piece quite easily without the attewntion to detail that Wiki and its contributors have rightly paid. Phil Ochs, after There But For Fortune, was never allowed to stray beyond my peripheral vision. It was far too great a song to have popped out by accident. He perhaps never achieved anything sles of similar gravitas. Folloping Phil´s deasth there came, fairly soon, a song by Tom Paxton, commemorating marking his friends´s demise. There is an awkward personal remorse in Paxton´s lyric in which he regrets that the last time he been in Phil´s company had been in a crowd all leaving an event together and distracted by someone lese in the crowds, he shouted a throwaway ¨See ya ´Phil`, over hiis shoulder as they went their sepepate ways.

The chorus of the song Tom susequnetly wrote was the hand-wringing, heart-breaking rhetorical recognition that Phil was ´gone by your own hand´ and you could almost see Tom sadly, bemusedly shaking his head as you listened to the line on the record, knowing that could never be an acceptable or sensible solution to the enigma.

A Nanci Griffith (right) track, that did not appear a few years later was truly haunintng. Her lyrics ask him ´what the hell´he was trying to say´in his. Her song suggests that people are whispering that he might be out there somewhere and laughing at us all. Radio Fragile is a perfectly titled song for one that is trying to work out and to put in context the energy and genius of Phil Ochs.

These are two great songs buy two great writers who nevertheless can only ask questions to which there ar no answers.

However, there has been validation of a kind for Phil Ochs. Join us tomorrow when we visit the Woody Guthrie Centre to learn more.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!