´MY BRUSH WAS MY WEAPON´ said Picasso

´MY BRUSH WAS MY WEAPON´ said Picasso

by Norman Warwick

Les Demoiselles d’Avignon ( The Young Ladies Of Avignon) left, is described by Singulart on-line magazine (that invites you to immerse yourself in art´) as a large oil painting by the Spanish artist Pablo Picasso. The work, part of the permanent collection of the Museum of Modern Art, portrays five nude female prostitutes in a brothel on Carrer d’Avinyó, a street in Barcelona. Each figure is depicted in a disconcerting confrontational manner and none is conventionally feminine. The women appear slightly menacing and are rendered with angular and disjointed body shapes. The figure on the left exhibits the facial features and dress of Egyptian or southern Asian style. The two adjacent figures are shown in the Iberian style of Picasso’s native Spain, while the two on the right are shown with African mask-like features. The ethnic primitivism evoked in these masks, according to Picasso, moved him to ´liberate an utterly original artistic style of compelling, even savage force.´

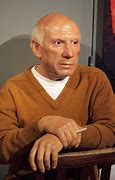

Completed by Pablo Picasso (right) in 1907, his oil on canvas Les Demoiselles d’Avignon became one of the most famous paintings in his catalogue, and a (sometimes controversial) landmark in the history of modern art.

Les Demoiselles d’Avignon is considered by many critics to be a prime example of the artist´s mastery of cubism. The artwork, nevertheless caused an uproar when first exhibited, as it depicted nude females in a non-traditional manner. More than a century later we might look back on the history of art and think that many artists before Picasso had made much and more of the nude female form. It was perhaps that these females are angular, unfeminine, and unflinching in their nudity. With this piece, Picasso aimed to establish himself as one of the great painters of his time, and the enduring response to the work has proved that he achieved that goal.

In the article I found, Singulart examines Picasso’s ´creation of the cubism movement´, the composition of Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, and why it continues to inspire debates and reactions to this day.

´While Picasso is most recognized for his cubist style´, the article began, ´his artistic career painting in the style of art nouveau and symbolism.´ In Barcelona, he was a regular visitor to the Els Quatre Gats café, meeting artists such as Henri Toulouse-Lautrec and Edvard Munch. These artists, along with close friend Jaime Sabartés, introduced Picasso to a cultural avant-garde movement, which would greatly inspire his art.

The death of Sabartés in 1901 inspired Pablo Picasso toward his blue period, during which he produced pieces like The Old Guitarist. In 1904, he moved onto his rose period, using a brighter colour palette of predominantly red and pink hues. His rose period was well-received (particularly compared to his blue period, which did not attract many buyers) and he soon received patronage from a number of wealthy clients.

Les Demoiselles d’Avignon was inspired by Iberian art, and the African influences can be seen in the mask-like visages of the figures on the right. Picasso had recently joined a gallery opened by art dealer Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler, he began to experiment with African influences in his art. His work showed the origins of the cubism movement through sharp, angular forms and monochromatic colours, Les Demoiselles d’Avignon is now considered to be the pioneering piece of the cubism art form.

Picasso continued to experiment with cubism, alongside fellow cubist artist Georges Braques. Picasso considered he and Braques to be ´two mountaineers, roped together, at once both collaborators and competitors. Together they pioneered the analyst cubist technique, taking objects apart and analyzing the shapes. Cubism artists rejected perspective, and avoided showing objects in a realistic way. The movement was furthered when Picasso and Braques began introducing other elements into their work, in what became known as synthetic cubism. The artists would incorporate materials such as newspaper and wallpaper into the pieces, experimenting with papier-colle.

Although the cubism movement faded in 1918 due to the growing influence of the surrealist movement, it experienced a resurgence in the nineteen twenties. The movement paved the way for other important movements such as art deco and minimalism.

Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, the painting under discussion in a recent episode of Genius: Picasso on tv in America, was inspired by Picasso’s intense desire to take Henri Matisse’s place as the painter at the centre of modern art. When Matisse exhibited Bonheur de Vivre at the 1907 Cézanne retrospective, it was heralded as one of the masterpieces of modern art and quickly snapped up by avid collector Gertrude Stein. Picasso’s competitive nature inspired him to create Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, which he hoped would inspire even more controversy than Bonheur de Vivre.

Les Demoiselles seems in direct opposition to the languid, fluid shapes of Bonheur de Vivre. We can see five women, prostitutes from a brothel on Carrer d’Avinyó in Barcelona, aggressively staring down the viewer. Three of the women have distinctly human faces, while the two figures on the left appear to have faces inspired by African masks.

The planes of Les Demoiselles are flattened, abandoning the Renaissance tradition of painting in a three-dimensional style. Picasso, quite literally, shattered this illusion as the women appear jagged and broken. For example, the woman on the left of the painting has a left leg that appears to have been painted as if viewed from many angles. Because the planes of the artwork are flattened, it is almost impossible to distinguish her leg from the background, blending the figures in with the colours surrounding them.

Picasso has painted these women in an arresting fashion. Standing at seven feet tall, they stare unflinchingly at the viewer, unashamed of their nakedness. Originally, Picasso had painted the woman on the left as a male medical student entering the brothel, but instead eventually chose to portray only women in the artwork. It is suggested that by removing a male presence from the artwork, the viewer becomes the ‘customer’ of these women; they are not confined to paying attention to a male within the artwork.

When first exhibited in July 1916, the work shocked and enraged audiences with its frank depiction of female nudity. A review published in Le Cri de Paris certainly didn´t mince words:

“The cubists are not waiting for the war to end to recommence hostilities against good sense. They are exhibiting at the Galerie Poiret naked women whose scattered parts are represented in all four corners of the canvas: here an eye, there an ear, over there a hand, a foot on top, a mouth below. M. Picasso, their leader, is possibly the least disheveled of the lot. He has painted, or rather daubed, five women who are, if the truth be told, all hacked up, and yet their limbs somehow manage to hold together. They have, moreover, piggish faces with eyes wandering negligently above their ears.”

As Picasso scholar Janie Cohen stated, “These women are looking right at us. And that was what was so outrageous about the painting. It frightened people. It made them angry.´

Somebody, it seems, should have lowered their eyes.

Even in recent years the work has faced controversy for supposedly displaying Picasso’s misogyny, painting these women just to serve the purpose of the male gaze.

Les Demoiselles d’Avignon by Pablo Picasso at The Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1939 © The Museum of MOdern Art ©2013 Estate of Pablo Picasso / Artist Rights Society (ARS)

Painting ‘ladies of the night’ was already a taboo subject, but Picasso took it to the extreme with his unapologetically naked prostitutes. Even Picasso’s friends and fellow artists were perturbed by the piece; Matisse, himself,, called it ´hideous´ and others assumed that, rather than a serious work, this was a crude joke. However, Picasso’s art dealer Daniel-Henry Kahnweller was supportive, writing in 1920:

´Early in 1907, Picasso began a large painting depicting women, fruit and drapery, which he left unfinished… The nudes, with large quiet eyes, stand rigid, like mannequins. Their stiff, round bodies are flesh-colored, black and white. That is the style of 1906. In the foreground, however, alien to the style of the rest of the painting, appear a crouching figure and a bowl of fruit. These forms are drawn angularly, not roundedly modeled in chiaroscuro. The colors are luscious blue, strident yellow, next to pure black and white. This is the beginning of Cubism, the first upsurge, a desperate titanic clash with all of the problems at once.´

Les Demoiselles d’Avignon is still as shocking and confrontational today as it was at its unveiling in 1916. Jonathon Jones wrote recently for The Guardian, that ´works of art settle down eventually, become respectable. But, 100 years on, Picasso’s is still so new, so troubling, it would be an insult to call it a masterpiece.´

So, a masterpiece, then, cannot be so called if ´troubling.´ To whom, and anyway, why not?

This year the painting it has also been shown a key element in an episode of Genius: Picasso.

photo 3 In a scene that plays tricks with time, we are shown young Picasso (played by Alex Rich) viewing African masks on display in a museum and then an older Picasso (Antonio Banderas) explaining to his protégé/lover Françoise Gilot how the masks inspired the Demoiselles. ´My brush was my weapon,´ he remembers realizing, as we see his younger self stir to action. ´My shield. My protector. I knew what to do.”

All this, actually part of an episode entitled vaguely as chapter five, reveals the older Picasso going to great lengths to convince Françoise Gilot (Clémence Poésy) to move in with him. Meanwhile, Young Pablo, struggling to match the genius of Matisse, finds dark inspiration from his souring relationship with Fernande Olivier played by Aisling Franciosi.

In the second installment of National Geographic Channel’s scripted anthology series, the famed artist, strikes up a flirtation with aspiring painter Françoise Gilot On one of her earliest visits to Picasso’s studio, in Paris, the discussion turns to the matter of inspiration, and effort, on which the aging lion offers wisdom gleaned from years of experience.

´The only way to be an artist is to work day and night—lose yourself in it completely,´ he says, ruefully. ´Do you have any idea how lonely that is?´

it was difficult to identify loneliness, reported Paste, on-line, at a recent, and very crowded press event at the Tribeca Film Festival, where the network erected a ´studio´ full of installations inspired by the defining periods of Picasso’s career, as well as futuristic digital easels for the public to toy with, but it was nevertheless clear that Banderas, 57, has thought as deeply about the subject of inspiration, and effort, as the artist he is playing and whom he calls his ´idol.´

´Inspiration has to come from 8 to 8,´ he said, before affecting a whine for comic effect. ´There’s no way that you can say, ‘I am not working today because I’m not inspired. I don’t feel it. It’s not coming to me today, and so I’ll be back tomorrow. I’ll be at the hotel.’

Antonio has served more than three decades in the acting business, including his fruitful, long-time collaboration with Spanish auteur Pedro Almodóvar, he has come to appreciate Picasso’s discipline—though his working hours were unorthodox, they were also quite routinized—without glossing over the complications this caused in the artist’s personal life, which are (as is the way these days) as much the focus of the TV series as his aesthetic innovations. It’s hard not to hear a note of recognition in Banderas’ voice when he says, after being asked about the foremost lesson he learned from playing Picasso, that ´really true artists suffer a great deal.´

´They don’t fit completely in their society, in the time, that they are living,´ Banderas continues. ´It requires a lot of sacrifices. (There are) misunderstandings with everybody else. A tremendous amount of honesty that works beautifully when you’re doing art—but that same honesty, it provokes a lot of problems, because we all travel through life with a mask, in a way.”

Banderas, of course. has played professional mask-wearer of Law of Desire, The Skin I Live In and, too, The Mask of Zorro, is far from suggesting that he’s prone to suffering, and he certainly doesn’t put on airs in the manner of an aging movie star, Paste seemed happy to point out.

´In fact´, says journalist Matt Brennan the actor was hospitalized following a heart attack in January 2017, ´but still shows the sprightliness of a much younger artist: At the start of each clip shown to the press at the Tribeca event, he leapt from his chair to get a better look—driven, if his body language is any indication, by genuine fascination with the final product. Still, when the award-winning performer—and, let’s face it, international sex symbol—offers his personal synopsis of the series, there’s no doubt that Banderas understands the pressures of fame that Picasso faced.

´Genius is… the portrait of a human being who suffers a pathology called ‘genius’ that affected very much the people that surrounded him and millions of people all around the world,´ he explains.

Picasso is, in enough senses to justify using the cliché, the role Banderas was born to play: He, like the artist, hails from Málaga, Spain, where he convinced show-runner Ken Biller to shoot several key scenes from Picasso’s early life in the actual locations they took place.

This was, he says, ´to capture the colours, the light, the shapes´ of Picasso’s formative years, but also to give the artist—who did not live to see the end of Francisco Franco’s dictatorship, and thus the end of his political exile in France—the Malagueño applause he deserved.

´That was beautiful,” Banderas (left) says of a scene on the beach with Picasso and his lover/muse/fellow artist, Dora Maar (Samantha Colley), which Biller filmed in Málaga despite it being set in the south of France, ´because I could just walk with Picasso in a place that he had never walked.´

The correspondences between Banderas and Picasso even informed other members of the cast and crew. In an uncommon move, Banderas and the actor Alex Rich were on set together throughout the production, despite never sharing the screen, so they could collaborate closely on matching their renditions of the man—though what Rich remembers as most daunting, referring to Banderas, was ´trying to sound like him—the sexiest voice on the planet.´

As make-up and hair designer Davina Lamont added at the festival, the point was not to transform Banderas into Picasso so much as seamlessly blend the two:

´I also wanted to have a little bit of Antonio in there,´ she says, and on that front she and the actor succeeded.

Though Banderas admits this meeting of performer and role was, at times, ´painful´ and that ´inhabiting (my) idol’s darker side was a particular challenge. At the festival, five weeks after wrapping the series,he admitted ´my mind is still confusing,´

He does, though, recognizes a fated-ness, or at least a fittingness, in Genius, one that comes through in the deftness of his depiction.

´This is the character that I have rejected the most in my life,´ Banderas says, noting that he’d turned down multiple offers to play Picasso in his twenties. Nevertheless, ít was impossible to say no [this] time. It was almost like I had to jump [off] a cliff… Picasso was kind of following me.´

Genius: Picasso shows on The National Geographic Channel

Steve Bewick´s latest Hot Biscuits jazz programme features an in depth look at Beverley Beirne’s `Dream Dancer` CD. We´ll be certain to check this show out because we have loved Beverley´s music ever since Steve introduced us to her work a while ago, and she has since featured on our pages at Sidedtracks And Detours The broadcast also features new sounds from Vega Trail, Phi Sonic, hania rani, Portico Quartet, Tim Garland’s Lighthouse and Matthew Halsall. If this sounds interesting then tell your friends and tune in 24/7 at https:.//mixcloud.com/stevebewick/

The prime source for this article was a piece written by Matt Brennan, tv editor for Paste on-line.

In our occasional re-postings Sidetracks And Detours are confident that we are not only sharing with our readers excellent articles written by experts but are also pointing to informed and informative sites readers will re-visit time and again. Of course, we feel sure our readers will also return to our daily not-for-profit knowing that we seek to provide core original material whilst sometimes spotlighting the best pieces from elsewhere, as we engage with genres and practitioners along all the sidetracks & detours we take.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!